Banks must understand the differences and intersectionalities between these to interpret and use the market signals that determine the credit risk status of sustainability projects.

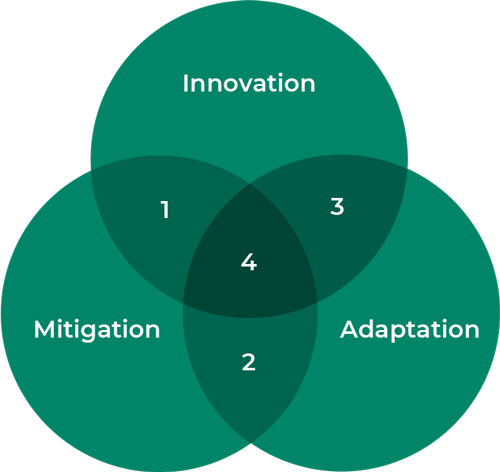

Meeting climate pathway targets needs Innovation, Adaptation, and Mitigation…

Climate change is happening, and its impacts are already being felt, from successively hotter years and decades to once-in-a-century floods becoming regular occurrences. As CO2 and other Greenhouse Gases (GHGs) are still being released at increasing annual rates, the scientific consensus is that, even if climate targets are ultimately met, extreme and volatile weather patterns must be viewed as part of life in the ‘new normal’.

This means that the world has to invest to adapt to consequences that are already locked into the system. Simultaneously, there is an urgent need to lower GHG emissions and to stay within the agreed carbon budget – the amount of CO2 or equivalent alternative gas (designated as CO2e) that can be emitted while limiting resultant global warming to specific targets. In order to remain within the carbon budget for a 2-degree rise in average global temperatures by 2100, investments in industries across the economic spectrum must be targeted towards more sustainable products and processes.

Innovation in both current industries and new technologies such as Carbon Capture and Sequestration (CCS), needs funding in the order of tens of trillions of dollars to meet the 2-degree global warming target and adapt the world to what just that increase means in terms of extreme weather.

Sustainability funding can be split between:

- New technologies and projects to actively prevent global warming. This will include new CCS designs, livestockfeed production, or alternate power generation such as solar, wind, or nuclear.

- Projects within existing firms to convert their operations to a more sustainable basis, using existing technology. This would include electrification of delivery fleets, carbon capture at coal-powered powerplants, and other process adaptations that prevent GHG emissions.

- Costs of projects to protect assets from the impacts of climate change that are already occurring or are most likely to occur. This will include innovative processes such as coastal defenses or agricultural land use.

- Financing projects that use new technology to not only protect assets but to actively stop further emissions. This can entail wholesale changes to business models, but also critically looks to adapt existing equipment and resources to be useful ina new greener economy.

Credit risk is inherent in sustainable investment, but even more so in doing nothing…

The fact that lending creates credit risk is encoded into obligor credit assessment practices as well as calculations they perform to estimate the amount of capital that needs to be held as High Quality Liquid Assets(HQLA), to insulate the banks from losses arising from potential defaults.

Climate change creates new and specific considerations in credit profiling. In addition to analysis of credit facilities in the context of the current economic environment, judgments need to be made considering possible future economic scenarios.

The International Panel for Climate Change (IPCC) produces pathways that will, if followed, lead to specified limits on global warming. These pathways are global by definition and necessity. Following the Conference of the Parties (COP) in 2015, convened in Paris, individual countries create their own targets for CO2e. These nations are also responsible for monitoring and reporting their own progress. COP26, in Glasgow, brought to light the fact that all ‘local’ plans combined are currently insufficient to reach the global goal. To make things worse, even these targets are not currently being met.

The inevitable conclusion is that plans will accelerate and present real challenges to firms working in impacted industries. Regulatory costs will rise in transport, building, energy, agriculture, infrastructure, and manufacturing, as countries increase pressure on their private sectors to lower their emissions. The slower the mitigation plans are put into place and run through the system, the greater the need for adaptation. In the common parlance of climate change pathways, a quickly implemented route to a 2030 milestone is referred to as an ‘orderly’ transition. The alternative is a ‘disorderly’ transition, where plans are slow to be created, instituted late, and cause increased economic disruption as well as allowing greater global warming to become inevitable.

Transition risk, which is defined as the risk to firms from climate regulation costs being too onerous for them to survive, becomes a key component for mid- and long-term financing analysis. Banks must build both transitional and physical risks to obligors’ assets into lending decisions and credit facility pricing.

Projects can be de-risked by government support…

Policy initiatives in areas like energy and agriculture indicate exactly where regulatory pressure will originate from. Instruments such as Border Carbon Agreements must also be taken into account as they effectively transfer climate policy costs from one economic regime to another.

Using all of these as the basis for climate-specific scenarios allows bankers to assess obligors in a way that shows likely future costs that will be incurred by firms that continue to operate in a non-sustainable manner.

An important area of government policy to examine is innovation funding. Both the EU and the US have specific programs, as does the UN.

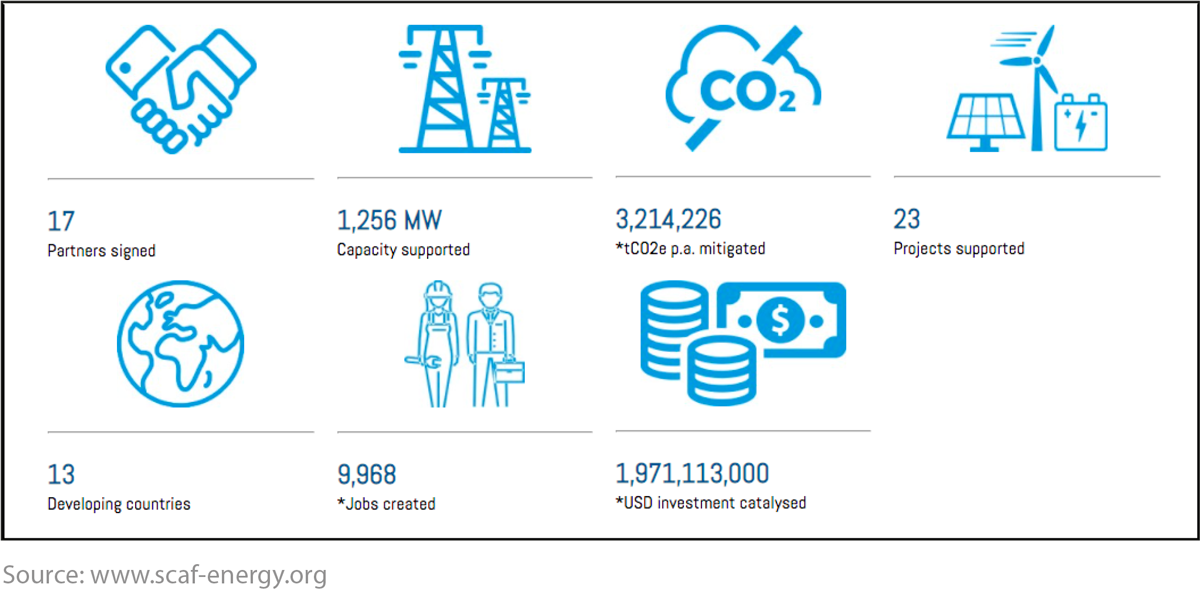

The UN’s Seed Capital Assistance Facility (SCAF) works with financing partners such as project development companies and private equity firms to de-risk early stages of innovative climate change mitigation projects, particularly in Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. The aim of SCAF is not to finance projects but to provide cost-sharing and co-financing with those partners, until projects aredemonstrably financially viable, at which point, other private financing takes over.

The European Green Deal also has an innovation fund, the aim of which is to provide EUR1.5 billion (in 2022) to ‘finance breakthrough technologies for renewable energy, energy-intensive industries, energy storage, andcarbon capture, use and storage’. The fund takes submissions annually, awarding EUR1 billion in 2021 acrossa range of approved projects.

In the US, the Biden/Harris administration announced a $100 million innovation fund from the Department of Energy (DoE), whose aims include:

- Zero net carbon buildings at zero net cost, including carbon-neutral construction materials Energy storage at one-tenth the cost of today’s alternatives

- Advanced energy system management tools to plan for and operate a grid powered by zero-carbon power plants

- Very low-cost zero-carbon on-road vehicles and transit systems

- New, sustainable fuels for aircraft and ships, as well as improvements in broader aircraft and ship efficiency and transportation management

- Affordable refrigeration, air-conditioning, and heat pumps made without refrigerants that warm the planet

- Carbon-free heat and industrial processes that capture emissions for making steel, concrete, chemicals, and other important industrial products

- Carbon-free hydrogen at a lower cost than hydrogen made from polluting alternatives

- Innovative soil management, plant biologies, and agricultural techniques to remove carbon dioxide from the air and store it in the ground

- Direct air capture systems and retrofits to existing industrial and power plant exhausts to capture carbon dioxide and use it to make alternative products or permanently sequester it deep underground

Banks can use the emergent innovation funding maps to divine pathway directionality…

Early investment in adaptation and mitigation will put firms in a position to avoid future regulatory costs and to gain market share as a new green economy. This advantage can be priced into such credit facilities, enablingbanks to incentivize sustainability across their balance sheets.

Examining where official innovation funding is being directed allows banks to make informed choices when building scenarios internally that replicate real-world pathways created by the IPCC.

These scenarios need to include economic impacts and be designed in such a way that industry and even loan-specific impacts can be included to reflect adaptations and investments that will lead to avoidance of climate transition risks and costs.

Understanding these impacts on customers and their business models allows banks to forecast any impacts on their own credit provisioning and even loan pricing. Loans to businesses with models that are resilient to expected transitional changes ought to attract preferential borrowing rates that reflect that resilience.

Under current banking regulations, to achieve this, a strong supporting analysis of climate risks is critical.

GreenCap can help…

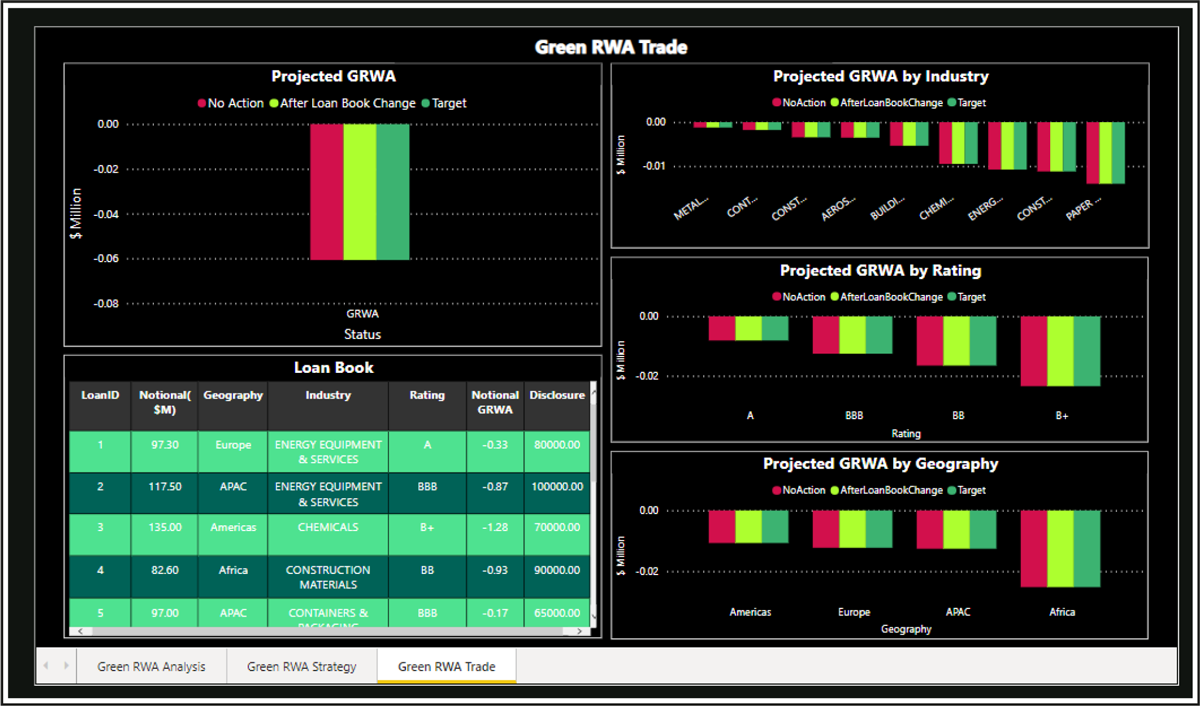

GreenCap is a Risk as a Service (RaaS) that was built to provide banks with the ability to design and shape economic scenarios in such a way that climate pathways, the speed at which they are implemented, and their impacts on customers’ credit profiles can be measured.

With GreenCap, banks can reliably predict the increases in credit-related capital provision they will face as global and regional climate plans are put into action. This can also be translated directly into loan pricing, giving banks the capacity to price sustainable incentives into loan facilities.