Climate pathways are a mix of adaptation and mitigation. Unexpected physical impacts and positive feedback loops will dictate prioritization of policy rollout.

Climate pathways are built on a range of predictive models…

Scientists engaged with climate change have been building effective potential climate pathways since the early 1990s. These are collated and curated by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), and are referred to as, ‘Representative Concentration Pathways’ (RCPs), indicating that the objective is to predict the building concentrations of Greenhouse Gases (GHGs) under various possible futures. RCPs run through to 2100 and are regularly updated to reflect the current status and final warming effect that would be achieved under each. The main RCPs used for scenario analysis are:

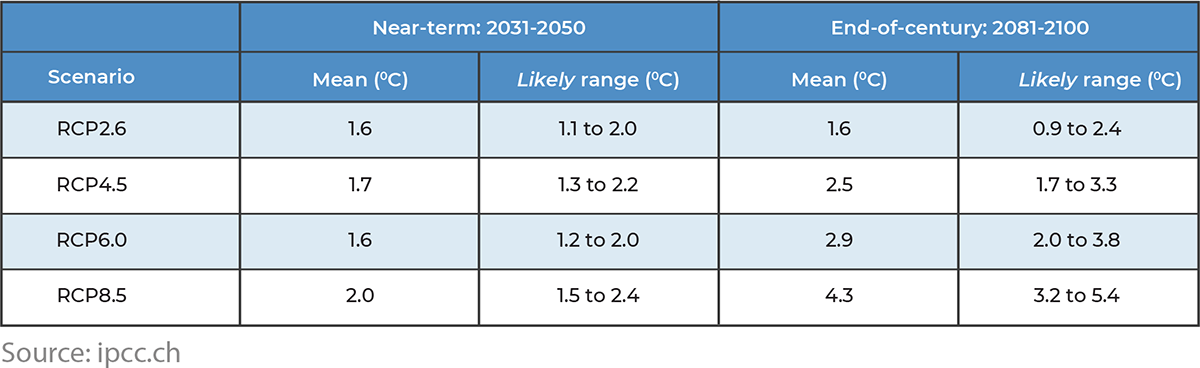

- RCP2.6 – Pathway that results in radiative forcing of 2.6 W/m2 2100. This is the pathway most commonly used as the target by the world’s governments at the Conferences of the Parties (COPs). It represents the level where most catastrophic global warming effects are avoided.

- RCP4.5 – Pathway that results in radiative forcing of 4.5 W/m2 2100. This is the lower end of the range where certain effects are felt, but with planned adaptation, can be ‘lived with’.

- RCP6.0 – Pathway that results in radiative forcing of 6.0 W/m2 2100. This is the higher end of the range where survivable effects are felt, but it is considered far worse than the 4.5 option as more ‘tipping points’ are encountered.

- RCP8.5 – Pathway that results in radiative forcing of 8.5 W/m2 2100. This is considered the equivalent of ‘business as usual’, with little effort being made to prevent the rise in global warming.

The IPCC produces advice for policymakers, based on observed and predicted climatic impacts, wherein they illustrate emergent and future risks along the pathways. The latest of these regarding sea levels is the 2019 ‘Special Report on the Oceans and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate’ (SROCC), which is of particular interest to governments when setting sustainability targets and forming their policy agendas.

The latest projections for the global mean surface temperature change, relative to 1850 -1900 averages, for each of the main RCPs, are:

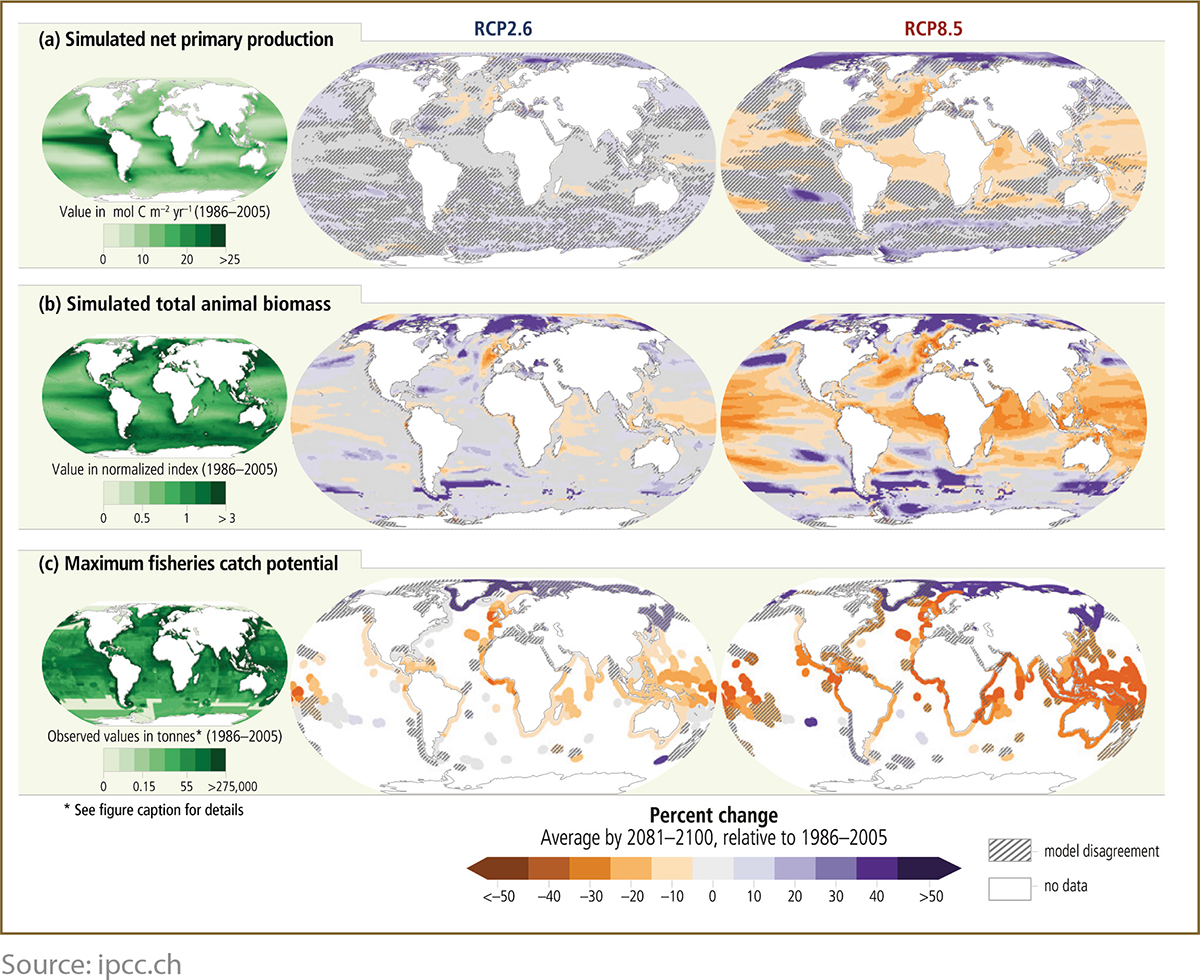

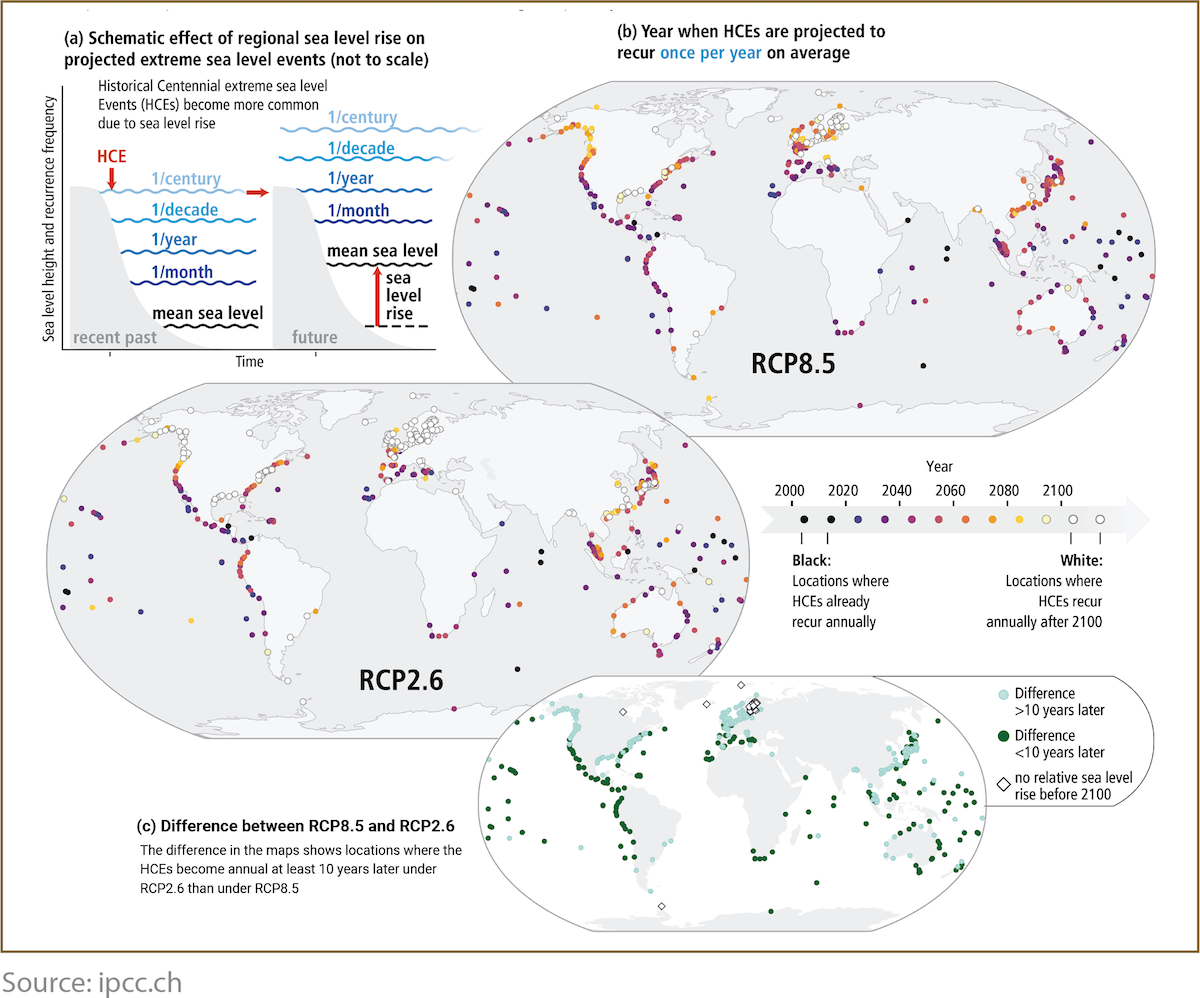

For analytic comparisons of rising sea levels and consequential hazards, the SROCC compares RCP 2.6 and 8.5. These comparisons illustrate the risks to oceans, coastal communities, and economies, which rely so heavily on them.

The differential impact of the RCPs on fisheries, as an example, is stark, creating both food production and economic issues for governments to take account of in their climate strategies.

Climate economics is also hinged on the balance between adaptation and mitigation. Less action in the short term on direct mitigation raises the likelihood of RCP8.5 and substantially increases the rate at which ‘Historically Centennial Events’ (HCEs) occur, which have a direct impact on the amount of climate-related budget that will be allocated to adaptation.

Effectively, the third global chart illustrates the additional ‘events’ that will require aid and funding, should the world elect to move slowly and allow itself to range towards RCP8.5 rather than RCP2.6.

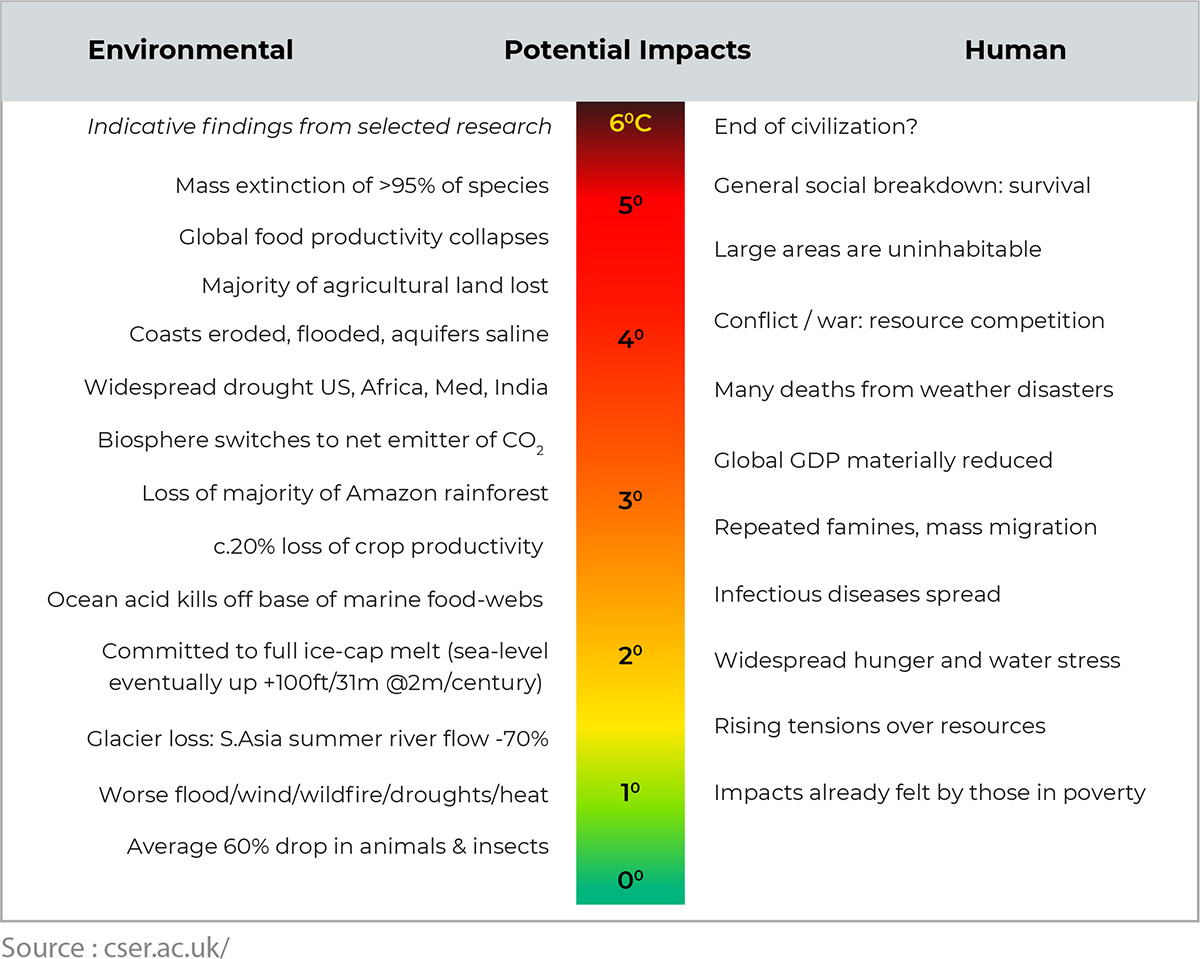

Outside of the IPCC, respected bodies such as Cambridge University’s ‘Centre for the Study of Existential Risk’ (CSER) have studied the environmental and societal impacts of rising temperatures during the current century.

Higher temperature ranges that result from slower, more passive, climate policies, create drastically higher risks and costs in the future, the prevention of which must inform shorter-term planning.

Governments provide indicators of their longer-term considerations…

The US government and military published two important documents in 2021.

The White House issued ‘The Report On The Impact Of Climate Change On Migration’, detailing concerns and required planning around:

- International aid to displaced peoples

- Dealing with impacts from increased US migration

- Technical support for identification and mitigation

- Financing mitigation and adaptation strategies

It is noted that geo-instability increases with rising global temperatures.

‘’Migration is an important form of adaptation to the impacts of climate change and in some cases, an essential response to climate threats to livelihoods and wellbeing; therefore, it requires careful management to ensure it is safe, orderly, and humane. It is critical to mitigate risks to the human security of migrants and receiving communities, such as risks to food and water security, access to necessary resources, and conflict at both the local and intercommunal levels. Large-scale migrations in response to destabilizing climate events within areas of particular economic or political importance can result in a disproportionate impact to a nation’s condition overall. This will likely be the case for the world’s coastal populations where sea level rise is predicted to displace a disproportionate number of people.’’

Source: White House Report on the Impact of Climate Change on Migration

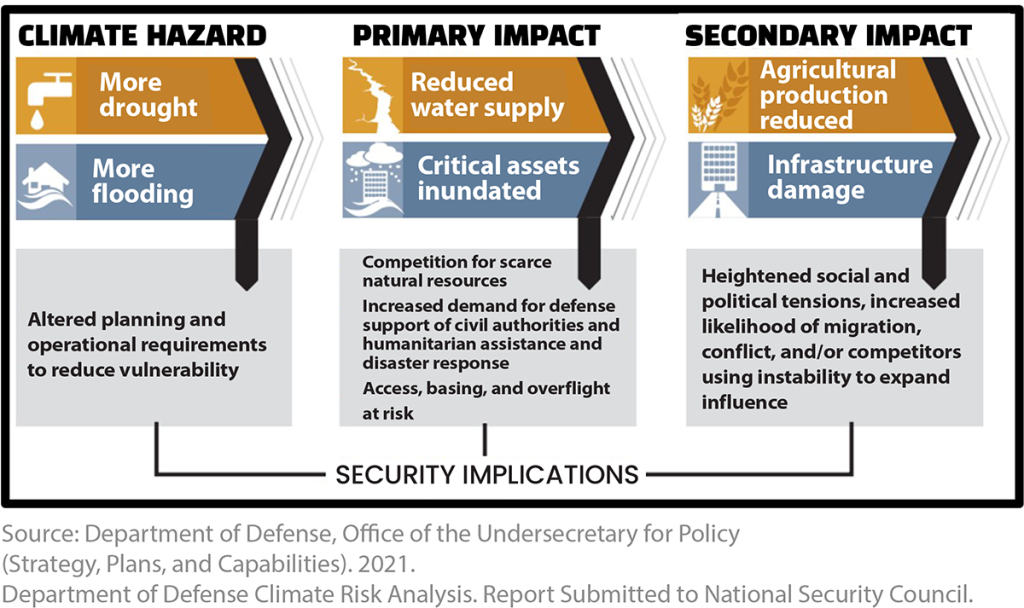

As the federal government detailed US concerns, the Pentagon also released its own report – ‘The Department of Defense Climate Risk Analysis’. In this publication, the US DoD details issues created by climate change, both within the US and abroad, along with its high-level plans to assist with the causes and effects.

It is increasingly clear that while climate change planning is primarily a domestic agenda, the wider global implications and impacts are being factored into decisions and budgeting around these plans.

Potential tipping points dictate the timing of specific climate measures…

Positive feedback loops within climate change are of particular concern to policymakers. A popular example is the ‘Methane Accelerator’, which was described by the World Business Academy in 2019, in their paper bearing that name. The publication explains how current levels of oceanic methane release put the world at considerable risk through:

- Global warming arising from CO2 emissions heats oceans and causes the release of trapped methane from the seafloor.

- Methane, while persisting for less time than CO2 in the atmosphere, is 84 times more potent as a heating agent.

- Increased methane concentration in the atmosphere speeds up the heating on the surface and oceans.

- Faster rising temperatures, caused in part by increasing methane concentrations, reduce ice coverage quicker than predicted, reducing the albedo effect (snow and ice are highly reflective and as such, reflect solar energy back into space) of the ice shelves.

- More solar energy retained in the atmosphere creates more heat to be absorbed by oceans, which in turn, speeds up the release of trapped methane.

- This positive feedback loop drastically reduces the time remaining for meaningful action to be taken to avoid the most catastrophic effects of global warming.

Governments aiming to protect their own countries and populations from the worst global impacts of climate change need to adjust policy and policy timing to avoid damaging positive feedback loops that threaten to undermine their best efforts at orderly transitions.

System thinking is needed to create effective, realistic scenarios…

Financing the global transition towards sustainability requires trillions of dollars from the private sector. Just as governments build transition plans that maintain physical, energy, and food security, banks must provide credit facilities that maintain their institutions and the financial system’s financial security.

This means that banks must continue to work within a regime governed by:

- IFRS9/CECL forces banks to hold accounting capital against conservatively estimated future credit losses

- Basel 3/Dodd Frank regulations put emphasis on the relationship between credit risk, liquidity, and financial stability

- Liquidity stress tests that ask banks to assess their internal liquidity in theoretically stressedeconomic conditions, and hold capital to survive these extremes

In order to be an effective conduit of sustainable finance, banks need to build economic scenarios that are equivalent to the RCPs and value their books against them. The issue that persists is the speed at which the RCP, or its regional counterpart, is enacted and the implied economic risks that this entails.

System thinking is where entire chains of effect are considered for analysis, with the system as a whole, being the focus rather than any single emission type or industry. When such thinking is applied to climate change, it becomes apparent that policy planning must include aspects of adaptation and mitigation, and policy priorities must be dictated by their longer-term feedback loop potentiality.

This implies that dealing with methane, and its greater heating potential may take greater priority than CO2. Banks need scenarios that reflect the RCPs at varying speeds and priorities that are and will become more urgent. This demands a bank climate stress testing system that is agile and can transform to reflect new research that can change policy, clearly showing how policy choices change credit risks and therefore a bank’s stability.

GreenCap can help…

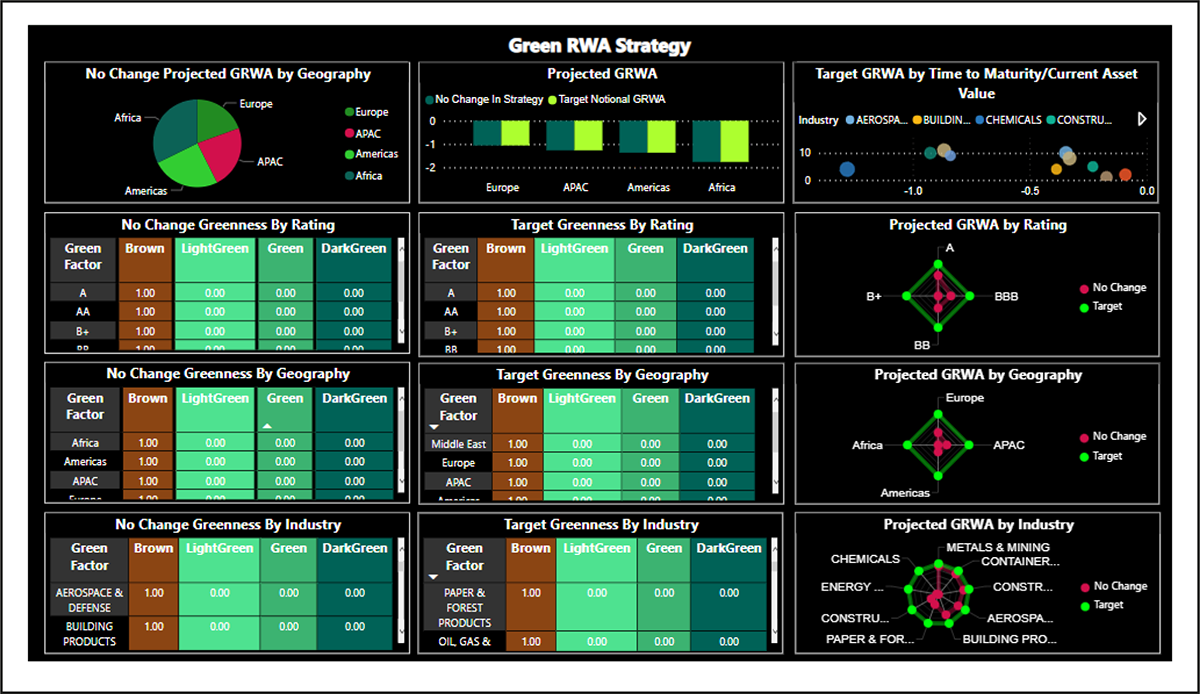

GreenCap is a Risk as a Service (RaaS) solution that is designed to supply banks with the capacity to build smart, climate-based scenarios that reflect the best estimates of bankers and scientists from the IPCC aswell as economists from the Net Greening of the Financial System (NGFS).

GreenCap models transition and physical-based credit risk and enables banks to adjust economic impacts for policy priorities. Using the system, bank risk teams can effectively build climate risk into their current frameworks and supply, reporting against climate-related risk targets to senior management for risk governance purposes.