The 2022 IPCC findings, along with the regulatory policy ideas from the sec, are required reading for banks building their climate risk programs.

The IPCC report, released on February 27 was alarming…

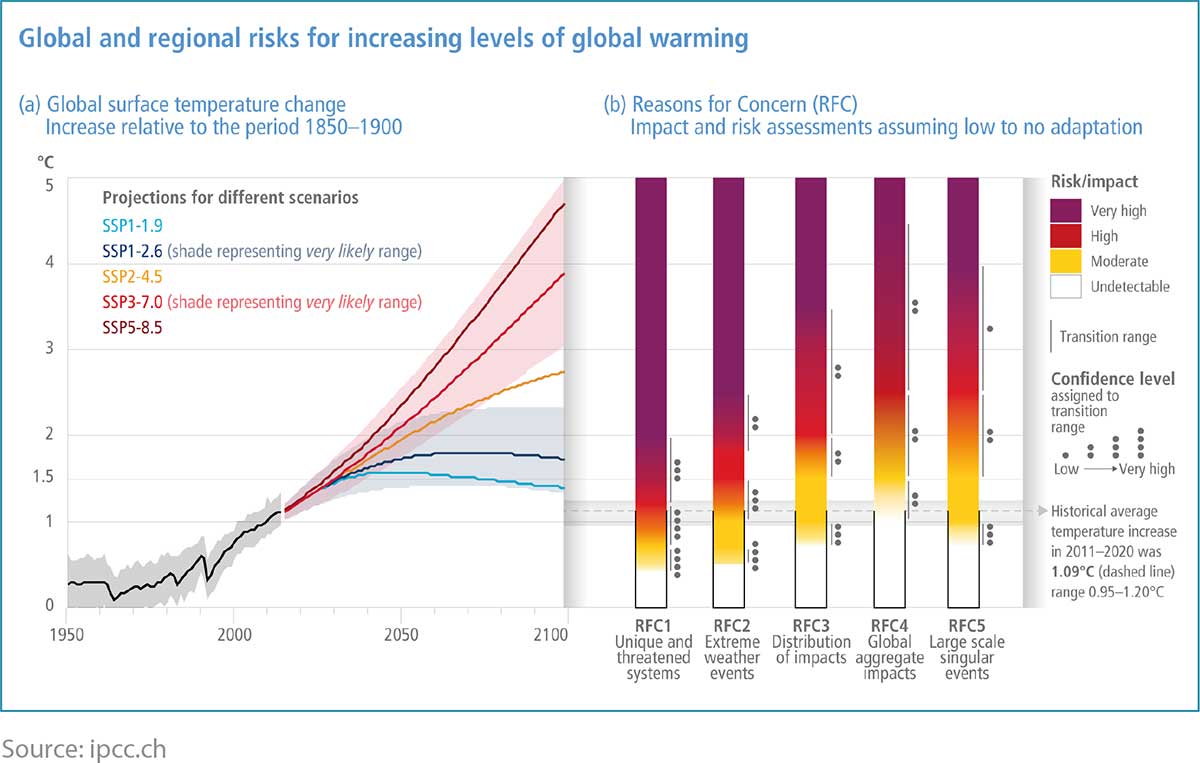

The long-term aim of the world’s governments, as agreed at the various Conferences of the Parties (COPs), has been to limit global warming by 2100, to 2 degrees above pre-industrial levels, with an effort made to achieve an even more ambitious limit of 1.5 degrees.

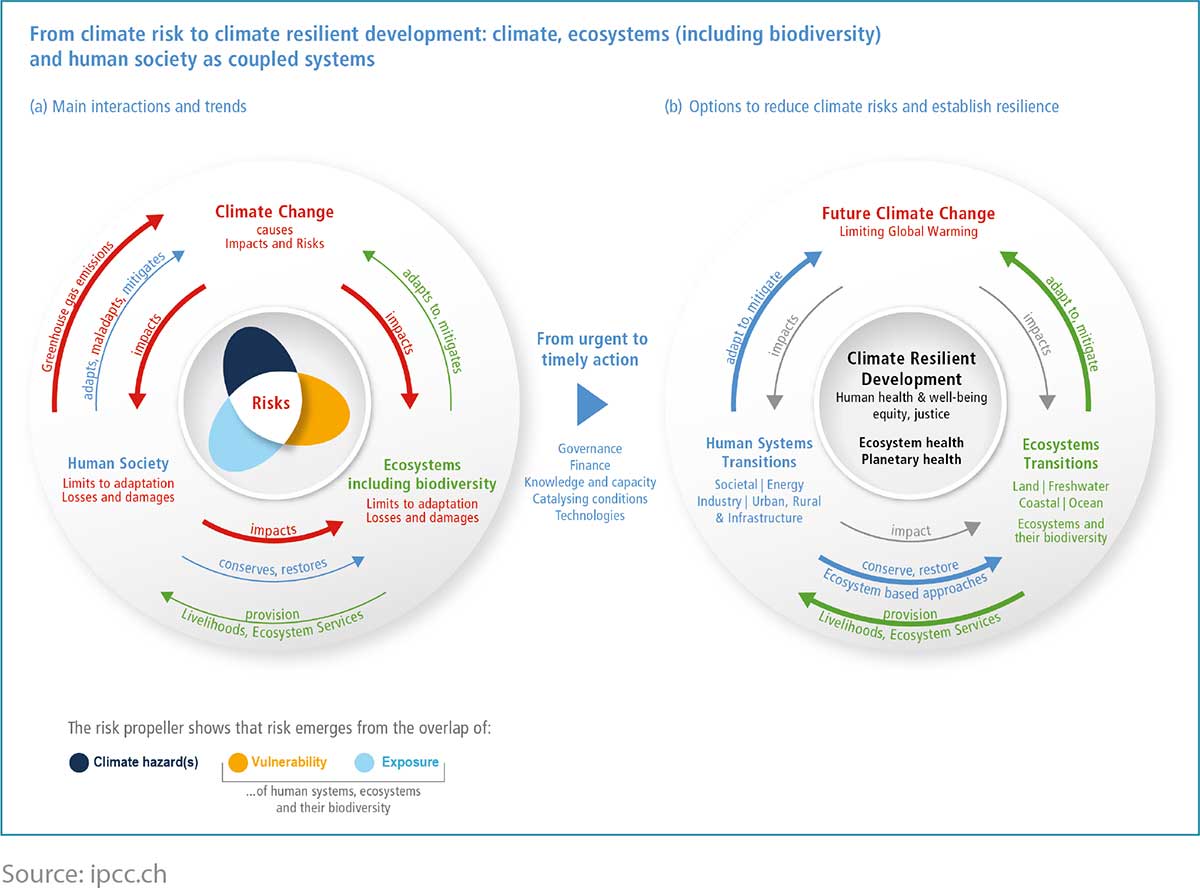

The recent report produced by the Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC) – Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability – was alarming, as it detailed how certain environmental tipping points had already been reached, and the need for adaptations to deal with consequences of ‘overshooting’ the 1.5-degree ‘soft’ target, may well dominate climate policy, with potentially dangerous implications.

Key points from the report include:

- Some previously possible pathways to avoid the worst consequences of climate change are already lost

- Global ecosystems are highly integrated with one another, meaning that acceptance of one tipping point significantly increases the probability of more following

- Any adaptation that is designed with short term goals to avoid specific risks, often leads to unintended consequences, giving rise to other risks becoming ‘Maladaptation’

Scientists contributing to the 2022 IPCC report have detailed specific risks that increase, byregion, as temperatures rise above the 1.5-degree limit.

These risks include:

| Small Islands |

|

| North America |

|

| Europe |

|

| Central and South America |

|

| Australasia |

|

| Asia |

|

| Africa |

|

The likelihood of these risks materializing varies considerably from region to region, but what is clear is that the overall risk rises substantially with higher endpoints in terms of global temperature rises.

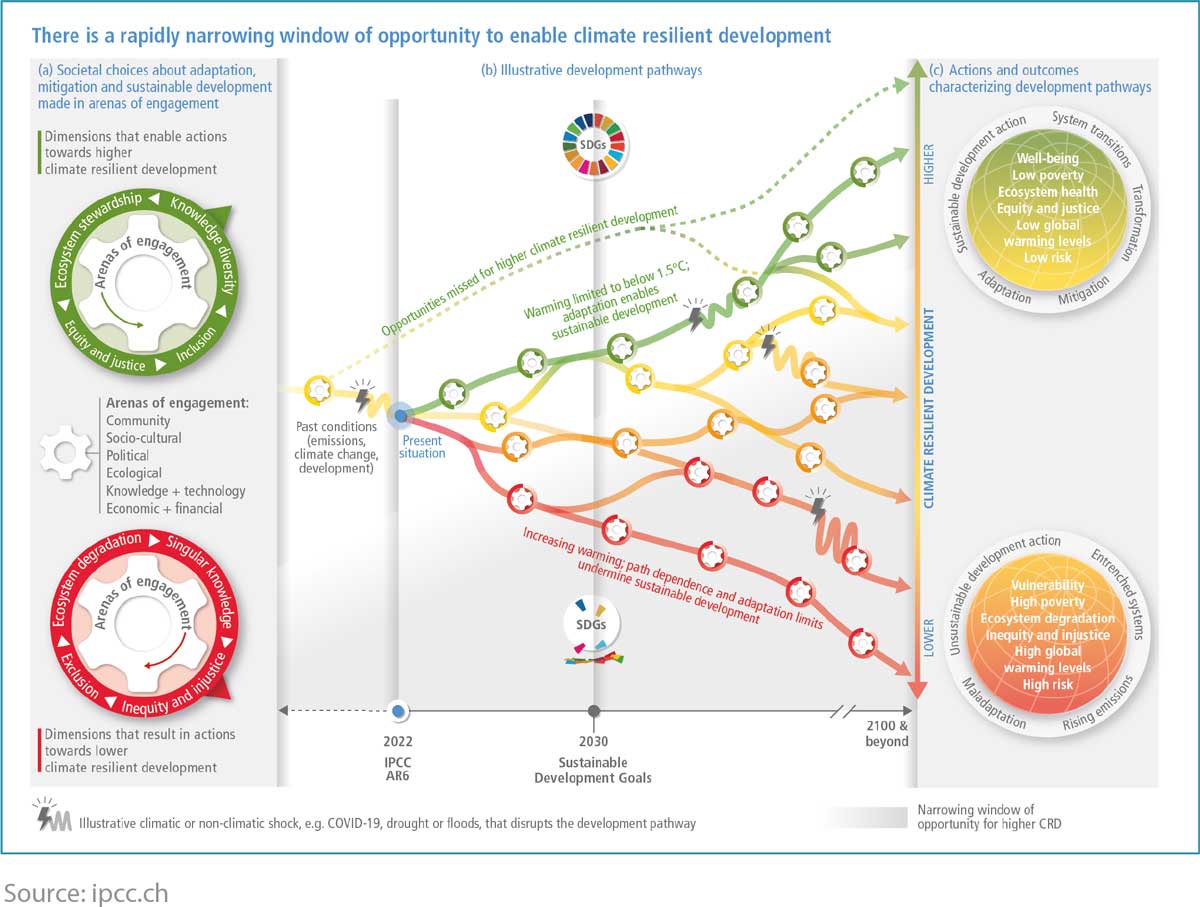

The current trajectory puts the world on a path where adaptation will become increasingly necessary, drawing more spending away from mitigation, creating more positive feedback loops. It also increases the likelihood of adaptation being rapid and not planned in a global, integrated fashion, possibly leading to maladaptation.

Pathways are continually reassessed and re-mapped, to reflect the latest ‘starting’ point. It is disturbingly clear that the probability of an outcome of a 1.5-degree temperature rise is vanishingly small and would require a massive increase in targets around the world, including almost instant policy changes to reflect that increase in ambition.

This has significant ramifications for banks’ climate stress scenarios…

Banks require stress tests to assess the resiliency of their own balance sheets. If they are to manage the vast financial flows required to mitigate and adapt, then they must be able to determine the resultant riskiness of current and future investments and credit facilities.

The rules around bank lending and credit risk, especially since the 2008 financial crisis, have been strengthened in ways, which mean that poor credit risk planning now could see far more risk capital beingheld, as their current obligors come to represent increased risks to the bank while effectively underpayingfor that risk in terms of interest rates and credit spreads.

Regulators, including the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), are creating policies that can assist climate risk managers…

The IPCC report was released three days after Russia invaded Ukraine, meaning that the full impact was less urgently reported than would normally have been the case. Even so, it is striking that the SEC released its climate change recommendations just three weeks later on March 21.

Interestingly, the SEC policies would fill an important data gap for banks building scenarios for stress-testing purposes.

Specifically, the paper calls for:

- Scope 1 and 2 disclosures from all filing companies

- Physical and transitional risk identification and quantification

- Upstream and downstream supply chain considerations

- Use and Impact of carbon pricing

Essentially, the recommendations, if bought into force, would move the US a lot closer to the EU in terms of climate change reporting.

Crucially, for banks looking to assess their balance sheet climate change risks, the new SEC policies would allow a process to be developed for the creation of likely scenarios built logically, including:

- Transitional plans based on the IPCC pathways and known government plans

- Costing of the known plans by the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), at a global and regional level

- Adjustments to scenario costs based on revisions to the IPCC report as well as International Energy Agency (IEA) progress reports

- Adjustments to scenario impact according to developing/likely carbon pricing and supply chain effects

The base ‘transitional’ scenario could then be enhanced to include physical impacts as also identified within the SEC requirements.

Finally, banks could use filings to determine those borrowers who had already taken steps to mitigate physical risks from climate change and adjust their exposure and future credit profiles accordingly. This would allow the development of strategies to green the balance sheet and properly price future climate-related credit risks into credit facility pricing.

Given the financial system’s central role in moving private money to projects and sectors where resilience is most needed, it is vital that banks perform this kind of scenario-based climate analysis both on their current book and future credit facilities.

GreenCap can help…

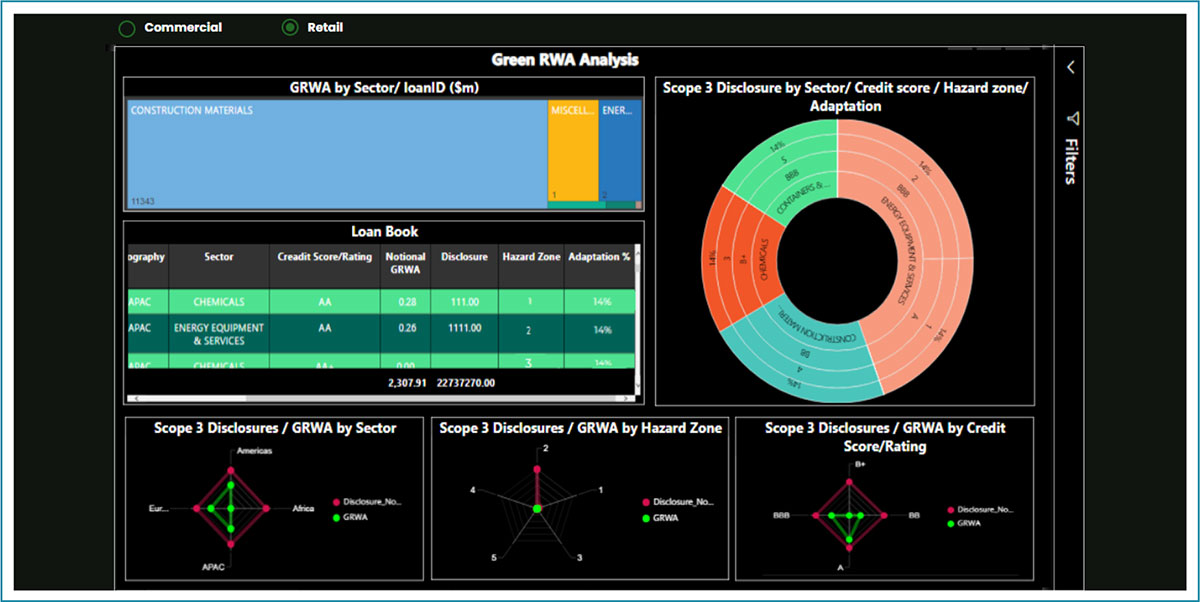

GreenCap is a turnkey ‘Risk as a Service’ (RaaS) solution that provides banks with tools to create and populate climate-based scenarios. These scenarios will reflect the impacts and costs of the IPCC pathways and regional plans.

The system provides loan by loan climate risk analysis, including potential increases in risk capital that should be expected per scenario, and the credit spread differential, in basis points, that would be needed to justify that risk.

GreenCap takes hazard zones and transitional adaptations into account, resulting in a granular analysis that uses all available data to provide insights that can be put to immediate use within the bank.