Understanding taxonomies, as well as differences between ESG and green bonds, is vital for banks to build sustainable balance sheets.

Green funding must meet specific criteria…

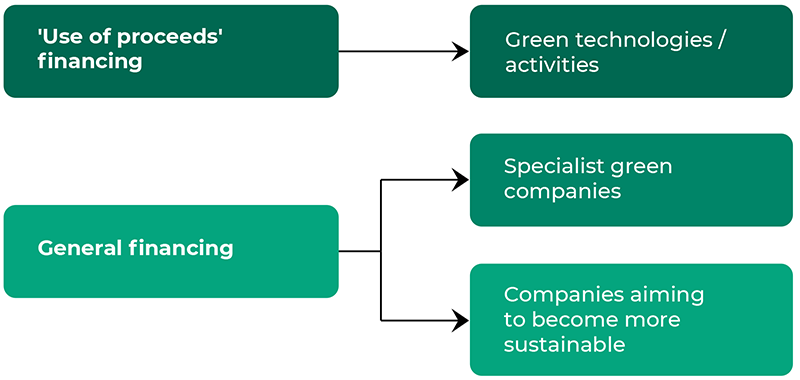

Along with the rise in awareness about climate change, comes an increasing desire from private finance to fund solutions to the adaptation and mitigation problems. There is no exact definition of what constitutes ‘green’ in terms of finance, but providers typically divide their funding recipients into distinct areas of interest:

- Technology/specific projects that target climate change mitigation or adaptation.

- Organizations that specialize in climate change prevention.

- Non-specialist organizations that are seeking to make their operations more sustainable.

These result in the need for credit facilities that are either:

- Targeted and defined with strict parameters about the precise use of funds.

- General financing with less stringent requirements on the use of funds.

In the context of a global economy that is shifting towards a greener future, the definition of green and how it fits into that envisioned future state becomes important for risk management purposes. Sustainable projects within organizations that strengthen their business model in the upcoming normal ought to be incentivized as they directly lower the credit risk profile of the borrower. One way to establish such a definition is to first explore various definitions of green bonds.

There are existing principles around green bonds…

The International Capital Markets Association (ICMA) publishes its Green Bond Principles (GBP). These establish four core alignment requirements as follows:

- Use of Proceeds

- Process for Project Evaluation and Selection

- Management of Proceeds

- Reporting

Use of proceeds refers to the inclusion of legal language into the framework to ensure that funds provided are used for sustainable projects. The association provides examples of such projects within the GBP.

- Renewable energy, including production, transmission, appliances, and products.

- Energy efficiency, new and refurbished buildings, energy storage, district heating, smart grids, appliances, and products.

- Pollution prevention and control, including reduction of air emissions, greenhouse gas control, soil remediation, waste prevention, waste reduction, waste recycling, and emission-efficient waste to energy.

- Environmentally sustainable management of living natural resources and land use, including environmentally sustainable agriculture, environmentally sustainable animal husbandry, climate-smart farm inputs such as biological crop protection or drip-irrigation, environmentally sustainable fishery and aquaculture, environmentally sustainable forestry, including afforestation or reforestation, and preservation or restoration of natural landscapes.

- Terrestrial and aquatic biodiversity conservation, including the protection of coastal, marine, and watershed environments.

- Clean transportation, such as electric, hybrid, public, rail, non-motorized, multi-modal transportation, infrastructure for clean energy vehicles, and reduction of harmful emissions.

- Sustainable water and wastewater management, including sustainable infrastructure for clean and/or drinking water, wastewater treatment, sustainable urban drainage systems and river training, and other forms of flooding mitigation.

- Climate change adaptation, including efforts to make infrastructure more resilient to impacts of climate change, as well as information support systems, such as climate observation, and early warning systems.

- Circular economy adapted products, production technologies and processes, such as the design of an introduction of reusable, recyclable, and refurbished materials, components and products, circular tools and services, and/or certified eco-efficient products.

- Green buildings that meet regional, national, or internationally recognized standards, or certifications for environmental performance.

Process for Project Evaluation and Selection means that an issuer of a Green Bond should clearly communicate:

- The environmental sustainability objectives of eligible Green Projects.

- The process by which the issuer determines how projects fit within eligible Green Projects categories (examples are identified above).

- Complementary information on processes by which the issuer identifies and manages perceived social and environmental risks associated with relevant project(s).

Management of Proceeds refers to the accounting of the project and usage of funds provided. Projects should be accounted for in a specific sub-portfolio and tracked by a formal internal process.

Reporting on the projects should be provided by the funding issuer, kept up to date, and be readily available to management. Annually, projects where funds have been used should be reported on, and where facility rollover is required, held to scrutiny against the original covenant.

The GBP is an excellent place to start when thinking about the exact definition of a green bond, but it does not always follow that the changing economic environment will mirror the sustainable ambitions of the bond issuers. From a credit risk perspective, green bonds defined against these principles may, but are not guaranteed to, achieve a lower credit risk profile as climate-related policies are announced and brought into law.

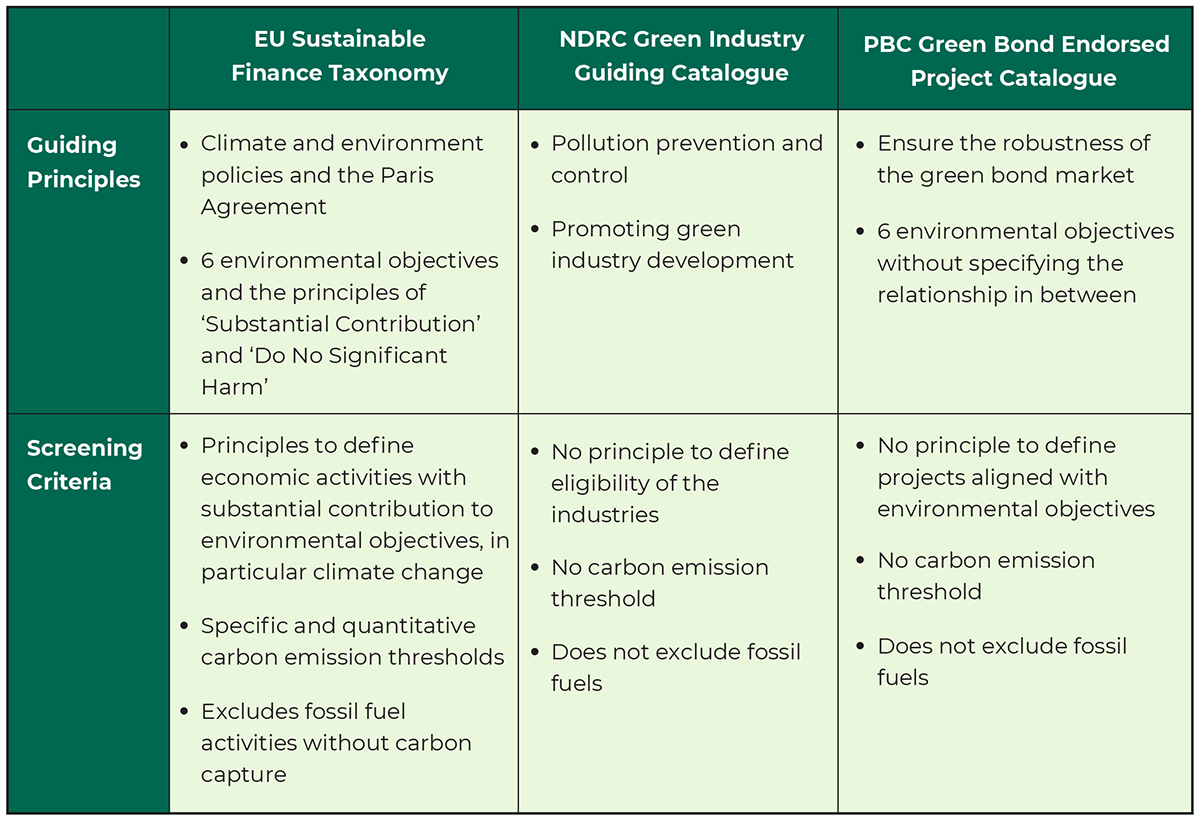

For bond definitions that are explicitly aligned to government objectives, we can explore the following taxonomies:

- Green Bond Endorsed Catalogue (People’s Bank of China)

- Sustainable Finance Taxonomy (European Union)

Both are intended to provide working definitions of green bonds that are in line with the climate policy objectives of the publishing governments. Given that these same governments are signatories at the annual Conference of the Parties (COPs), there should be alignment between scientifically endorsed mitigation projects, policies, and green bond definitions. It is this alignment that makes these beneficial when linking green loan pricing, risk management and use of loan proceeds.

Before looking at that explicit link, though, it is important to recognize that there are some differences between these taxonomies.

The six environmental objectives of the EU taxonomy are defined as:

- Climate change mitigation

- Climate change adaptation

- Sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources

- Transition to a circular economy

- Waste prevention and recycling

- Pollution prevention and control

- Protection of healthy ecosystems

These are completely aligned with that bloc’s ‘Green Deal’ high level aims.

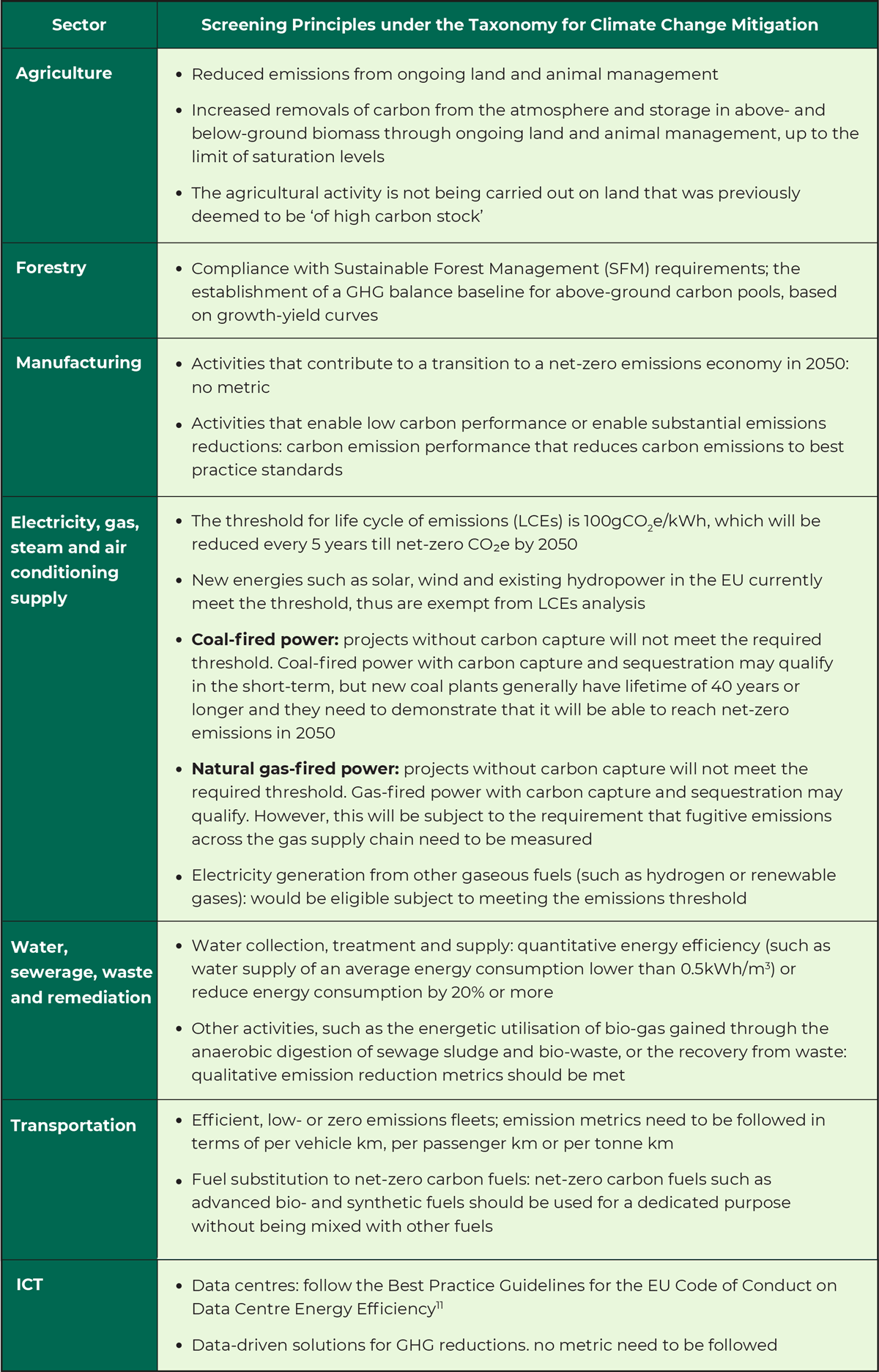

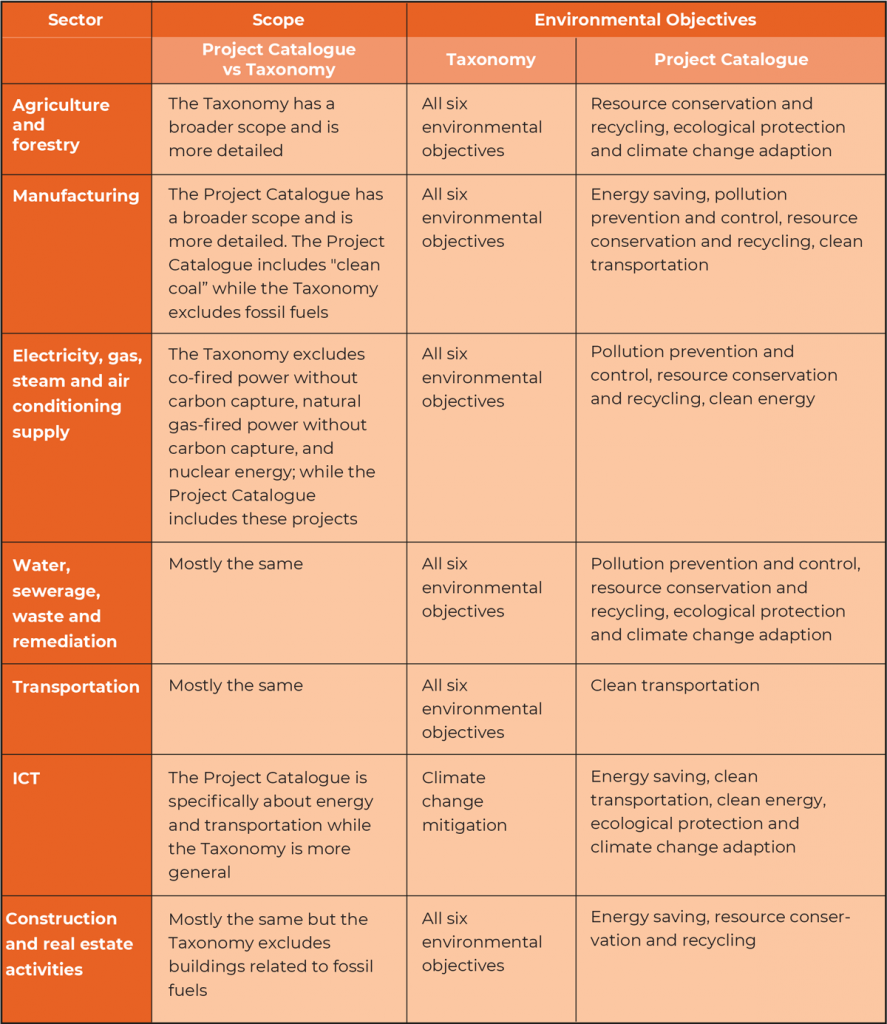

To compare the Chinese and European classification schemes, the following list of environmental screening criteria is used.

With these definitions in mind, the following table shows how the two schemas differ.

Although there are substantial differences, the point remains that projects that meet these definitions, within the regions they are applicable, will correspond to policies created to meet the ambitions of that government. Therefore, they will benefit from an increasingly benign economic climate.

ESG bonds may be green, but they are not green bonds…

It should be noted that there is a wider world of ESG bonds in the modern market. To align with climate-change mitigation policy, it is only specifically ‘green’ loans and bonds that are considered in this article.

Greenness of the bond is definitively linked to its forward credit profile…

As mentioned in the previous sections, aligning credit facilities with policies, aimed at mitigating climate change, will have a knock-on effect of reducing the credit risk profile of the borrower.

The reverse is also true. Financing projects and firms that will find themselves targeted by expensive regulation, or their business models made redundant by environmental laws, can only see credit risk across the balance sheet rise exponentially.

Green principles must be adopted for general loan governance…

Banks are faced with risks and opportunities in the emerging green economy.

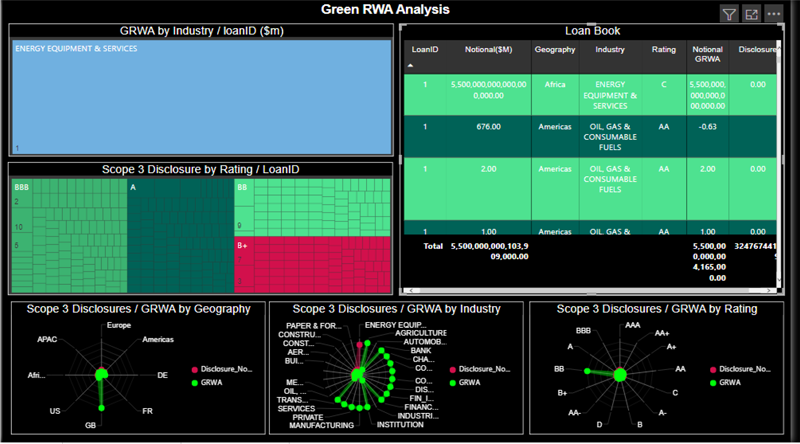

The main risk is that their loan books incur increasing credit risk charges due to the Risk Weighted Asset (RWA) calculation causing more capital to be held in low return, safe assets, or High Quality Liquid Assets (HQLA). Holding a higher percentage of capital in these assets directly decreases profitability, as less capital is ‘working’ in the market.

Related to the RWA increase is the pricing of loans. Higher credit risk is typically accompanied by a higher spread on the loan itself. The problem with climate change risk is that loans and credit facilities are often long-term, with the rate set in the current ‘brown’ economic environment. Offsetting spreads need to be set for the future, against the most predictable climate-impacted economic environment.

Banks have to create frameworks and protocols now, to ensure that they remain liquid as the coming decade of climate policy initiatives unfolds.

GreenCap can help…

GreenCap is a ‘Risk As A Service’ system that empowers banks with the capacity to include climate change into their loan pricing and credit risk analytics.

GreenCap:

- Builds specific Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) climate pathways into pricing and risk analytics.

- Allows banks to price adaptation and mitigation into current and future credit pricing.

- Enables climate-related strategies to be developed by the bank.

- Deals with transition (policy-based) and physical climate risks.

- Provides sustainability reporting at the CFO level.